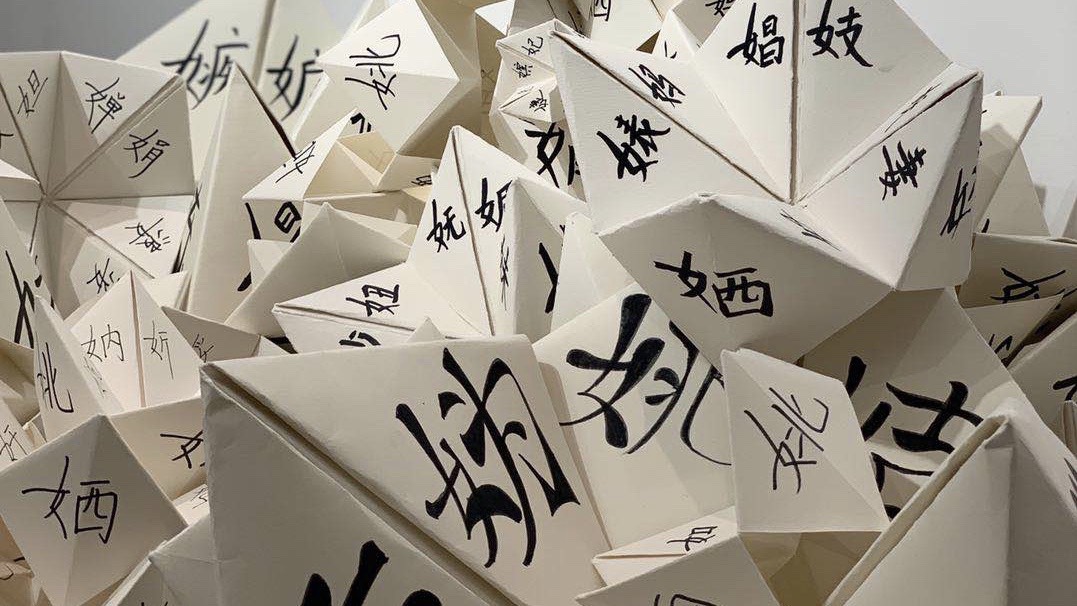

Image credit: Cherry Blossom/Sky, by Annie Qu

by Cao Yi Er

Read the Faculty Introduction.

Welcome to the Art Exhibit

She went to an art exhibition yesterday.

Before she left for the art exhibition, she spent hours on her makeup, covering her dark circles and pimples that arose from the pressures of work and life. Among her piles of cheap belongings, she carefully picked out a Burberry dress, Chanel jewelry, Dior high heels, and an Hermes handbag, which she rented for the art exhibition. She put them on, stood in front of the mirror, and took a gorgeous selfie. The messy background of her old and small apartment looked weird compared to her well-dressed appearance.

She frowned at her apartment, but was satisfied with her outfit.

She walked out of her apartment, which was situated in an old and shabby neighborhood. She was too glamorous to fit in that environment.

I don’t belong here, she said to herself, grabbing “her” Hermes handbag tightly.

At the art exhibition, she wandered around, unable to appreciate the artworks.

She started to feel a bit bored, but a luxurious Rolex watch caught her eyes. Then she noticed the young man wearing the Rolex watch. She quietly followed him and observed the young man for a while.

He must be a rich and well-educated man, she concluded.

She went directly to him. “Incredible painting, isn’t it?” she asked.

The man looked at her, quickly scanned her from top to bottom, and answered, “Yes. Shall we walk around together?”

The conversation went on fluently, though they barely talked about art. As she expected, the man invited her for dinner.

She walked out of the exhibition, only to find he drove a BMW car. She felt angry and deceived.

How dare a man with a BMW flirt with me and ask to date me?

She dumped the man immediately after the dinner, turned to her WeChat group chat called “Shanghai Ladies,” and complained about her experience.

“Sis, men driving BMWs are stingy! I thought he drove a Ferrari! He was such a fraud!”

“Yeah! Many diaosi (men who are poor) are seeking for baifumei (women who are rich and beautiful) in art exhibitions now.”

“Ewww, men like that suck!”

The above anecdote is not fictional, but based on a true story adapted from a conversation from the WeChat group chat called “Shanghai Ladies.” From the conversation, it is apparent that by pretending to be beautiful and rich, a girl tried to attract rich men, but was upset due to him not being rich as she expected, despite her lying to him.

Meet the Ladies

In the traditional sense, the term “Shanghai Lady” refers to young women who are native to Shanghai and come from upper-class families with prominent social status. Nurtured in such families, they often enjoy a high quality of life and opportunities to receive an elite education, thus growing into cultivated and virtuous ladies. Obviously, the girl in the anecdote is not a “Shanghai Lady” in the traditional sense. She and other girls like her are called the “Shanghai Ladies” and have been a topic of heated discussion ever since the release of a WeChat article on Oct 11, 2020, “我潜伏上海“名媛”群,做了半个月的名媛观察者” (“I hid in Shanghai Ladies group chat, and observed them for half a month,” translated by Yi Er Cao), written by investigative journalist Li Zhonger. In order to gain some insight into this special social group, Li pretended to be a young lady and joined a WeChat group consisting of the so-called Shanghai Ladies. According to the post, Li paid ¥500 to be admitted because the group claimed to be available only for socialites to make friends and share resources like the latest news about luxury and fashion (Li). However, after he joined the group, he found out that the Shanghai Ladies group chat is just a platform for buying or renting luxurious goods and services by splitting the costs. The group chat members then take turns using the luxurious products, like Hermes handbags, in order to take photos with them (Li).

From the conversation in the WeChat post (Fig 1), it is clear that the women in the group chat live an upper-class life at the lowest costs by split buying and renting extravagances (Li). Four people each paying ¥350 can rent a Hermes bag for a month and each uses the bag for one week (Shanghai Ladies). Six people can enjoy a ¥500 high tea by paying ¥85 each (Shanghai Ladies). 40 people paying ¥125 each can afford a night in the ¥5000 Bulgari Hotel (Shanghai Ladies). 60 people paying ¥100 each can rent a Ferrari for one day (Shanghai Ladies). Even a pair of ¥600 second-hand Gucci stockings has been divided into 4 splits (Shanghai Ladies).

During their temporary ownership of various luxuries, the women take photos, post them online, and equip themselves for a social life of pretending to be rich. Through splitting costs via the group chat, they can temporarily be perceived as Shanghai Ladies in the traditional sense. This unique phenomenon of renting a wealthy look thus leads to several essential questions: Why do the women in the group chat attempt to construct their identities as upper-class? By what methods do Shanghai Ladies achieve class mobility with borrowed luxury goods? Most importantly, can membership in the Shanghai Ladies group chat truly help these women achieve class mobility?

This research paper seeks to answer those questions in order to look into the phenomenon of the Shanghai Ladies group chat members It is not hard to see that the reason why the Shanghai Ladies disguise themselves as upper class women is to achieve social class mobility and enter a higher social class through two potential methods: virtual class mobility and a more traditional mobility through marriage. On one hand, the Shanghai Ladies construct a false upper class identity online by taking photos of themselves living luxurious lifestyles with name brand products and posting the photos on social media. This online activity can be thought of as virtual class mobility. It is accomplished through receiving likes on their photos, which indicates that the women may be perceived as being upper class through recognition and approval from their followers. On the other hand, the Shanghai Ladies must split costs to rent or buy luxurious items and make themselves look wealthy in person to potentially attract and marry upper-class men. These practices in offline identity construction are often utilized to achieve social class mobility through a more traditional way: to find a rich male partner and share the property through marriage.

However, virtual and traditional class mobility do not really work because Shanghai Ladies only focus on superficial social capitals like receiving “likes” online, rather than cultural capitals like institutionalized education and knowledge. This may create a quandary between the identity and the self. The phenomenon of the Shanghai Ladies group chat reflects a new mode of establishing one’s identity, the struggle of women from lower social class in China, and the conflict between material desires and sustaining the true self.

This phenomenon goes beyond the Shanghai Ladies’ aspirations of class mobility; it reflects an external social issue of how we treat people who falsify their identity online. When this phenomenon was first investigated and exposed online, Li’s article was flooded with comments containing moral criticisms from the public, which later evolved into bullying for the Shanghai Ladies’ dishonesty and supposed vanity. This negative reaction from the masses is worth examining, as it reveals a sense of moral superiority on behalf of the online users who taunted the Shanghai Ladies. Through sociologist Steph Lawler’s theories of dual identities in “Getting Out and Getting Away: Women’s Narratives of Class Mobility,” the quandaries that the women encounter with class mobility will be explored and discussed in order to examine social responses to Shanghai Ladies.

Who Are the Shanghai Ladies?

Technically, the women in the group chat are not Shanghainese. They come from low-class families and poor regions in the proximity of Shanghai, aspiring to migrate to and make a living in Shanghai, a modern city full of opportunities. Due to their deficiency in education and knowledge, they could only take on minor-paid jobs, which can just sustain their basic life needs. Undeniably, the luxurious lifestyles and consumptions are far beyond what these women can afford. Therefore, they found a way to approach their dreams of living luxurious lifestyles, which was to be in the group chat “Shanghai Ladies.”

In a conversation between a Shanghai Lady’s ex-boyfriend and Li, the author of “我潜伏上海“名媛”群,做了半个月的名媛观察者” (“I went undercover in Shanghai Ladies group chat, and observed them for half a month,” translated by Yi Er Cao), the ex-boyfriend depicts how his ex-girlfriend was deceived into the group chat. To join the group chat, she made a fake certificate of deposit, and turned to her boyfriend to borrow the ¥500 admission fee. Apparently, she was pursuing a lifestyle that is far beyond her consumption capacity.

So, what life are the Shanghai Ladies truly living? To better understand this, it is important to have a general knowledge of the social environment in Shanghai. According to China Statistical Yearbook 2021 compiled by National Bureau of Statistics of China, the average monthly salary in Shanghai is ¥14,323, while the average personal consumption in Shanghai is ¥3,544. The life the Shanghai Ladies are truly living can be seen from another investigative article “‘上海名媛群’女孩回应:心里住着灰姑娘,一元包邮买发圈”(“Response From Shanghai ladies: We are Cinderella internally,” translated by Yi Er Cao), in which a journalist interviews Fei Fei, a member of the Shanghai Ladies group chat, to learn more about the Shanghai Ladies. According to the conversation, Fei Fei works as a saleswoman and lives in a small apartment in a peripheral region in Shanghai. She earns an average salary of ¥5,000 Chinese yuan every month (approximately $789 USD), which sustains her lifestyle of purchasing basic necessities, using public transportation, and eating little to sustain a low weight and save money (Shanghai Ladies). The money she earns only meets her daily expenditures, substantially limiting her access to luxurious products and services. Enjoying high tea in a deluxe hotel, wearing Chanel clothes, and carrying Hermes bags were simply unreachable dreams to someone earning Fei Fei’s salary. When she learned that she could enjoy those luxuries at low costs, she paid the admissions fee without hesitation and joined the group chat. By renting or splitting, she temporarily indulged herself in being a member of the upper class.

Overall, Fei Fei’s interview illuminates some common features of members of the Shanghai Ladies group chat. They come from lower class families and work ordinary and low paid jobs because of their limited education. They are already striving to make a living in a modern city, but are still aspiring to live an upper-class lifestyle.

Identity Construction and Class Mobility

To begin, the Shanghai Ladies’ possession of luxury may be a way of constructing their ideal or desired identity in the social sphere. Associate Professors of Marketing Grubb and Grathwohl’s article “Consumer Self-Concept, Symbolism and Market Behavior: A Theoretical Approach” proposes that “if a product is to serve as a symbolic communication device it must achieve social recognition, and the meaning associated with the product must be clearly established and understood by related segments of society” (24). As a symbolic communication device, possessing luxury items signals the owner’s fortune and social status, especially items with high prices and limited availability. It is commonly known that members of the upper class are more than able to purchase and use luxury items. They share knowledge of what kind of dressings they should be wearing, in what manner they should behave, and what kind of quality life they should be living. Therefore, if a person is living an upper-class lifestyle, they are likely to “achieve social recognition” and be accepted as upper-class (Grubb and Grathwohl 24).

Naturally, the aforementioned norms of owning luxury items are used when judging and assuming someone’s economic class status. Basically, the ownership of luxury or luxurious lifestyle becomes one of the differentiating standards used to identify the upper class from people earning an average salary. Thinking back to the anecdote, the Shanghai Lady was judging men according to what watch they wore. The watch brand was what she cared about the most before ever engaging with the man. This situation exemplifies the idea that “when the identity through appearance is considered, the actor (person) uses possessions like clothing, ornaments, and/or other products and brands to define his/her identity”; personal belongings are important hints of identity and social class when it comes to being a Shanghai Lady (Çadırcı and Güngör 271). By wearing luxurious clothes, carrying brand-name bags, and enjoying a high tea, Shanghai Ladies label themselves with these typical features of the upper class, behaving in their way even though they may never be capable of affording such modes of life. On one hand, by pretending and acting like upper-class women everyday, they may gradually convince themselves that they are members of this imagined identity. On the other hand, with these items signaling wealth, they can be perceived by other social members as upper class. Thereby, to some degree, they do succeed in constructing their identity as upper class women.

Furthermore, though temporarily owning luxury products may satisfy her desire to both present as and be perceived as rich, a Shanghai Ladies’ ultimate goal is to achieve class mobility through marriage into a higher class. In the conversation in the group chat, it is notable that “to take photos” is frequently expressed by Shanghai Ladies (Shanghai Ladies). They will take photos of themselves when they look like members of the upper class and are enjoying luxurious lifestyles, and then post the photos on social media like Weibo, RED, and WeChat Moments. It is stated in “Love My Selfie: selfies in managing impressions on social networks” that people “need affirmation” to “build an aggregate extended self together with friends, peers, and others” (Çadırcı and Güngör 273). This can account for the Shanghai Ladies’ behaviors of posting photos online, as it may help them manage their online personas as upper-class women. When representing themselves in social networking, they may gain admiration and envy from their friends, thus contributing to their self-esteem and superiority. Fei Fei, the Shanghai Lady, always gets many “likes” as well as some “jealous talking” when she posts photos presenting her constructed upper-class self on WeChat Moments: “朋友圈给我点赞的人突然多了起来。开始还有个别人疯言疯语,我直接就屏蔽了。现在随便一发都是几十个赞。只能说有钱真好!” (“People who like my posts on WeChat suddenly increase a lot. At the beginning, there were some people talking nonsense, I just blocked them. Now I easily get many ‘likes’ when I post. Being Wealthy is great!” Translated by Yi Er Cao). The “likes” and attention on social media are potential advantages for the Shanghai Ladies who use borrowed luxury items to construct their false online identity as a rich woman. In this way, they may achieve virtual class mobility: class mobility achieved through online affirmations that demonstrate other people perceiving them as genuinely rich “Shanghai Ladies.” However, achieving this recognition of being rich happens online and cognitionally. At the core, this “class mobility” is just a facade rooted in social media attention. The illusionary class mobility doesn’t turn their upper-class ambitions into reality. Instead, as shown by Fei Fei’s interview, what it does bring is online flattering and emotional fulfillment, which may tempt them deeper into self-deception and greed. This temptation is one of the many quandaries to be explored later.

Aside from virtual class mobility, some screenshots of the Shanghai Ladies’ conversations demonstrate their ambitions to move to a higher social class by marriage. As illustrated by the anecdote, Shanghai Ladies try to attract rich men in settings like art exhibitions to date them so that they can get expensive presents from them and even marry them, sharing the property and wealth. Ironically, they may feel deceived if the man they attract is not as wealthy as they expect because they have totally persuaded themselves into their imaginary identity. Admittedly, some men may be cheated into the false identity and marry them. Nevertheless, can lies about the Shanghai Ladies identity sustain love and marriage?

Quandary in Class Mobility

As inspected in the last section, Shanghai Ladies are already caught up in a dilemma between identity construction and class mobility, which arises from the gap between imagined upper-class identity and reality. The gap may give rise to shame of one’s self and identity. Evidence can be found in Lawler’s research “‘Getting out and Getting Away:’ Women’s Narratives of Class Mobility” on women who have gone through class mobility and moved to a higher class, where she discovers that women share a sense of shame related to their self and identity. In other words, Lawler’s research indicates that this may be because they feel like they can never be naturalized into the upper-class. Lawler also points out that “although these women have acquired a measure of symbolic and cultural capitals, they have not inherited these capitals, but ‘bought’ them within systems of education and training, or through the relationship of their adult lives” (13).

In other words, social class is not merely judged on material capitals, such as property like money and estates, it also requires cultural capitals like disposition, knowledge, taste, lifestyles that are acquired through long-term family and institutionalized education (Lawler 5). In other words, cultural capital implies how someone was nurtured from their birth and actually speaks louder for their social class. For example, during an interview conducted by Lawler, a woman expressed concern about her incapacity to speak French (15). This can be analogous to the incapacity to speak standard Mandarin without an accent in China, while another woman pointed out her lack of knowledge that comes from traveling and a decent education. Although women from the lower class can acquire new capitals through education and marriage, they “express a sense of cultural inadequacy and incompetency” and “relate the sense to class inequality” (Lawler 15). They do not intrinsically belong to the upper class, especially when class mobility is achieved through marriage, which doesn’t guarantee their eternal possession of capital considering the possibility of divorce. Thereby, women from lower social class may find it hard to understand upper-class life modes and habits. Women who achieved class mobility keep finding themselves conflicted by their new upper class status, thus having a low estimation of self and a sense of inferiority (Lawler 16).

In addition to experiencing a sense of inferiority, women tend to get caught up in “the gap between being and seeming” (Lawler 16). Class mobility leads to women having a dual identity: their former lower class status and current upper class status. This duality leads to a dilemma due to being unsure which identity is the “true self,” which is significant as the source of one’s sense of belonging (16). It is recorded in Lawler’s conversation that, when women have moved to the upper class, it is inevitable for them to meet their family members, who are still situated in the lower social class (16). Their interactions with their families expose them to the unerasable past as lower class, which reinforces their awareness of the inadequacy that derives from past life (16). Thus, this sense of inadequacy induces shame and confusion about which is the “true self.” This phenomenon is particularly common in China. Women work so hard to escape from the original social status and live a better life, nevertheless, they are overwhelmed with the guilt of abandoning the original identity because of their affection for their family. For the new identity, they spare no efforts to naturalize and internalize it, but they may be interrupted by the memory of the past and inherent deficiency in cultural capital, which comprises a person’s social assets such as education or travel experience (16). As Lawler explains, the two identities are so intertwined and inseparable that they lose the sense of belongings to either (16). The lack of an authentic sense of belonging can generate insecurity and shame, leaving them at a loss.

Aside from internal suffering, women are meanwhile under intentional and unintentional gazes and examinations externally. To move to a higher class, women need to struggle to fit in, be recognized and accepted by people who naturally belong to the upper class. Therefore, they may experience “moments when they were shamed by (the real or imagined) judgment of others” (Lawler 13). It is notable that others’ judgments can be real, but also can be imagined. Imagined judgments mainly come from women’s inferiority and sensitivity, and any minor expression or behavior that means no offense may be sensitively perceived and wrongly interpreted by women because of shame of self. Real judgments can be made intentionally by the public. For instance, one common type of judgment imposed on women revolves around how women achieve class mobility, whether they depend on their own capacity or depend on a man’s wealth, which they attract with their beauty. Also, women are culturally obliged to return to their family, give birth to children, and support the family rather than develop their own career. Such social norms are interwoven into women’s lives, attaching them to a family rather than allowing them to be an independent individual. After the Shanghai Ladies issue was exposed online, many people took to the internet to harass and degrade the women for their actions, casting an even darker light on their ambitions for class mobility.

Backlash Against Class Mobility Dreams: Social Response and Implications

After the publication of the WeChat article, the public learned of the existence of the Shanghai Ladies group and their absurd lifestyles. Nonetheless, the exposure of the Shanghai Ladies and their lifestyles points to a bigger issue of women’s class mobility. They are undertaking great pressure in pursuit of the upper social class, which is often futile due to their online actions that result in virtual class mobility and are dependent on superficial social capital. Aside from being ashamed of and confused by their identity, they are faced with overwhelming social opinions. Therefore, when exploring the Shanghai Ladies phenomenon, it is essential to be more understanding, empathetic, and considerate of the quandaries they are going through while attempting to achieve class mobility. Therefore, the Shanghai Ladies, from their class ambitions to their internal identity issues, may serve as inspiration to inspect our online actions carefully. To create a better social environment for struggling women, it is important to meticulously inspect ourselves and the social environment in Shanghai.

Nowadays, social media functions as an effective platform for disclosure with a wide reach of audience, the Shanghai Ladies’ dishonesty placed them at risk of being exposed as they were in the WeChat article “我潜伏上海“名媛”群,做了半个月的名媛观察者” (“I hid in Shanghai Ladies group chat, and observed them for half a month,” Translated by Yi Er Cao). After the Shanghai Ladies were revealed, the public reacted negatively to them. Users flooded the comments on the article: “Anyone split a boyfriend with me?” “Anyone split a down jacket with me? I use it in winter, and you use it in the rest of the year.” “No wonder there are so many young rich girls online, they are all so fake” (Shanghai Ladies). The public made fun of their ways of splitting purchases and renting luxury items. They laughed at their fake identity and vain dreams of marrying upper-class men. On the surface, the sharp criticisms may have represented people’s desire to signal their superiority over the women. Nonetheless, at a deeper level, the criticism may indicate the commenters’ inferiority. Before Shanghai Ladies were exposed, WeChat users would like and comment on their posts, some expressing their admiration, some doubting because of jealousy. However, upon learning the truth, people’s comments turned sarcastic. In the interview, Fei Fei expressed her dismay that she was using her money rather than stealing from anyone else or violating the law, which was her freedom to determine how and where to use her money (“Response from ‘Shanghai Ladies’, 2010). She couldn’t understand why people were being so harsh to them, using sarcastic words to bully them (“Response from ‘Shanghai Ladies’, 2010). It is worth affirming that however inappropriate the Shanghai Ladies’ measures are, they are still legal methods to achieve class mobility.

In the video “对上海名媛指责过后,我发现错误在我 (“After blaming Shanghai Ladies, I find mistakes lie in myself,” Translated by Yi Er Cao) made by Xiang Luo, a famous professor and director of the Institute of Criminal Law of the China University of Political Science and Law, he points out that when making moral judgments on Shanghai Ladies, we shouldn’t forget to examine ourselves (00:53). People may criticize Shanghai Ladies for showing off the luxury which doesn’t belong to them on social media, but they should ask themselves as well, are they also showing off something in their daily lives? On social media, some people show off their wealth and reputation, while some show off their indifference to fame and fortune; some show off their popularity and social networking, while some show off their knowledge or high-quality diploma (01:11). In other words, in response to the Shanghai Ladies, people are subconsciously showing off their superiority of virtue by delivering sharp criticism of Shanghai Ladies. As a consequence, the public are more or less committed with such moral corruption, pursuing something vain like Shanghai Ladies. Luo also maintains that on one hand, people gain a sense of self-satisfaction through criticizing others’ mistakes, which frees us from regretting and repenting our own mistakes (01:30). People tend to vent their indignation and hatred to a small group, acting as an innocent judger. Luo’s work helps illuminate that the Shanghai Ladies were exposed and targeted by people who may have felt that they could blame the Shanghai Ladies so that they didn’t have to take the responsibility for such moral corruption.

In light of Luo’s review on moral superiority, as a social member, what can an individual do to counter this social trend? From my perspective, it is preferred to be more critical of one’s self instead of others. Any criticism should finally lead to self-inspection and self-reflection. Are we reinforcing the stereotype of the upper class by attaching importance to luxury? Are we reinforcing sexist stereotypes of women by assuming their class mobility is the result of depending on men? Are we contributing to the social pressure on women? These are some deeply rooted dilemmas and stereotypes that help construct the social class system, which is hard or impossible to eliminate. If our social participation is dominated by sharp criticism, we will inevitably become Internet troll, or people who often engage in online quarrels. These reflections may not only effectively prevent us from becoming blindly cynical critics and bullies when mistakes happen, but also potentially make us rational and sensible thinkers who learn from past mistakes and look forward to the future.

Conclusion: Let Bubbles Touch the Sky

The Shanghai Ladies issue was sensational news. The disclosure of the group chat’s true nature exposed the Shanghai Ladies’ fake identities, evoked social indignation and criticism, and triggered discussions about identity, morality, and socio-economic mobility. The Shanghai Ladies constructed false upper class identities both online and in person by renting and splitting costs of luxury goods. Their methods of virtual and traditional (via marriage) class mobility were often unsustainable, leading some women like Fei Fei to feel caught up in an internal dilemma between the construction of their imagined identity and their actual low-income status. This gap often led to shame, and when exposed, their shame was exacerbated by criticism from a judgemental online community. Both the internal quandary and external online bullying emphasize that many people are often attempting to signal something, whether it’s wealth like the Shanghai Ladies, or a sense of false virtue, like those who shamed the women for pretending to be rich.

The class mobility dreams of Shanghai Ladies are reminiscent of bubbles. Bubbles look colorful and shiny externally, easily floating up to the sky. However, they will never touch the sky because as they approach the sky, they are too fragile to undertake the pressure, destined to break and disappear momentarily. Like bubbles, the Shanghai Ladies dream of flying to the sky, moving to a higher class. As they get closer to the upper class, they will find their dreams so vulnerable that they are destined to burst into nothing because they simplify the idea of the upper class into superficial capital and are faced with the potential quandary of dual identity. They may never achieve mobility unless they rely on themselves to make a living and develop cultural capitals at the same time. They may fortunately ride a wind to fly higher, but they eventually have to undertake the consequences of lying and, potentially, a bursted bubble of a class dream.

Addendum: Translation of Pictures

Works Cited

Çadırcı, Tuğçe Ozansoy and Ayşegül Sağkaya Güngör. “Love my selfie: selfies in managing impressions on social networks.” Journal of Marketing Communications, vol. 25, no. 3, 2019, pp. 268-287, doi: 10.1080/13527266.2016.1249390

Grubb, Edward L., and Harrison L. Grathwohl. “Consumer Self-Concept, Symbolism and Market Behavior: A Theoretical Approach.” Journal of Marketing, vol. 31, no. 4, 1967, pp. 22–27. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1249461. Accessed 20 Nov. 2020.

Lawler, Steph. “ ‘Getting out and Getting Away’: Women’s Narratives of Class Mobility.” Feminist Review, no. 63, 1999, pp. 3–24. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/1395585. Accessed 6 Nov. 2020.

Li, Zhonger, “wo qianfu shanghai mingyuanqun, zuole bangeyuede mingyuan guanchazhe 我潜伏上海“名媛”群,做了半个月的名媛观察者” [I hid in “Shanghai Ladies” group chat, and observed them for half a month]. 12 Oct. 2020. https://finance.sina.com.cn/chanjing/gsnews/2020-10-12/doc-iivhvpwz1636883.shtml

Luo, Xiang. “Dui shanghai mingyuan zhize guo hou, wofaxian cuowu zaiwo 对上海名媛指责过后,我发现错误在我” [After blaming Shanghai Ladies, I find mistakes lie in myself], bilibili. Web. 16 Oct. 2020, https://www.bilibili.com/video/BV1Mv411k788

National Bureau of Statistics of China, China Statistical Yearbook 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/ndsj/2021/indexch.htm

“Shanghai mingyuanqun nvhai huiying: xinli zhuzhe huiguniang yiyuan baoyou maifaquan上海名媛群女孩回应:心里住着灰姑娘,一元包邮买发圈” [Response From ‘Shanghai Ladies’: We are Cinderalla internally] 网易. Web. 14 Oct. 2020: https://www.163.com/dy/article/FOT18DMV0525CHJG.html

Image credit: Girl Looking Up, by Ryan Ouyang