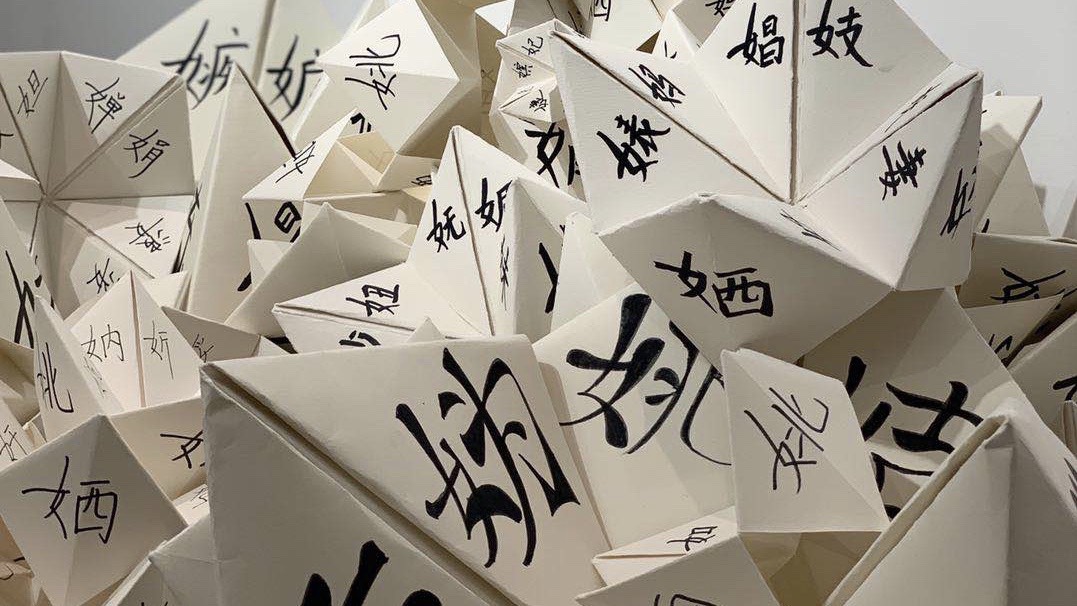

Image credit: 东南西北, by Yin Le

by Li Qinci

Read the Faculty Introduction.

In his comedy The Taming of the Shrew, William Shakespeare portrays how Katherine, under the taming of her husband Petruchio, transforms from a shrewish contrarian to a deferential wife like her sister Bianca. However, Katherine’s dramatic reformation, accompanied by the comedy’s ridiculous and playful tone, undermines the credibility of her submission; Taming thus becomes more like a satire, poking fun at men’s wishful celebration of women’s ostensible subjugation. Similar dubiousness towards women’s submission also exists in Lessons for Women, a survival guide for newlywed wives composed by Ban Zhao, the first female historian in the Han Dynasty. When we reexamine Taming through the window of Ban Zhao’s work, specifically, where she persuades women to defer to men in language, we discover that, together with Bianca who has already tamed her language upon appearing on stage, Katherine exemplifies “linguistic taming”— a series of strategies available for women in response to overwhelming patriarchal pressure — through linguistic disguise, avoiding verbal confrontations, and strategically adopting silence. More importantly, as Katherine gradually transforms her language from bellicose to forbearing, she also undergoes an inner voyage from aggressive self-isolation from the patriarchy, to liberated self-acceptance. Thus, linguistic taming, especially for headstrong women like Katherine, not only empowers them to manipulate their male partners for power alliances within the patriarchy, but also alleviates the tension between their strong personalities and external societal pressure.

Despite their cultural differences, the Elizabethan Era (1558–1603) under Shakespeare’s pen bears startling similarities in terms of gender relations with the Han Dynasty in Ban Zhao’s narratives (45–114). Notably, both societies advocate reticence as a virtue for women. In Lessons, Ban Zhao exhorts women to cultivate “womanly virtue” by speaking only “at appropriate times; and not weary others (with too much conversation),” which illuminates how women’s use of language predominantly affects their perceived moral characters (184-185). Similarly, in Taming, Bianca’s future husband Lucentio first notices her silence during their initial encounter, marveling that “in [Bianca’s] silence do I see maid’s milkd behavior and sobriety” (I.i.71-72). Here, Lucentio associates Bianca’s silence with her sobriety, confirming the correlation between a woman’s words and character. Additionally, in both societies, a husband’s dignity will suffer due to his wife’s disobedience. As Ban Zhao pinpoints, a husband’s incompetence to control his wife indicates his own unworthiness (181). Correspondingly, in Taming, after losing the wager on their spouses’ obedience due to Bianca’s defiance, Lucentio blames his beloved wife for making him a “fool” (V.ii.143). His unusual wrath highlights that a husband’s level of competence to tame his wife functions as a barometer of his intelligence and masculinity. In light of these similarities in social background, the instructions from Lessons on when to speak, what to speak, and how to speak provide a good theoretical framework for interpreting Bianca and Katherine’s true motivations behind their words in Taming.

Whether Ban Zhao promotes women’s wholehearted submission to men in Lessons has engendered controversy in modern and contemporary Chinese feminism debate. In renowned Chinese feminist He-Yin Zhen’s essay “On the Revenge of Women,” she castigates Lessons and condemns Ban Zhao as “a slave of men” and “an archtraitor to women” (Liu 145). However, to capture Ban Zhao’s true intentions, we need to examine her political career and lyric ode Traveling Eastward. After her student Empress Dowager Deng took on the role of regent, Ban Zhao took the position of Deng’s backroom counselor to assist her in governing the state (Swann 41). Such tacit support for Deng’s matriarchy not only demonstrates Ban Zhao’s ambition to exert influence on politics, but also indicates her approval of women’s dominance over men. In addition, in her ode Traveling Eastward, Ban Zhao unreservedly expresses her desire for “benevolence,” “reciprocity,” and “uprightness,” virtues that Confucianism permits only gentlemen to pursue (Swann 116). For instance, Ban Zhao acknowledges that “genuine virtue cannot die; though the body decay, the name lives on” (Swann 114). Thus, even though she “[knows] that man’s nature and destiny rest with Heaven,” she still believes that “by effort we can go forward and draw near to benevolence” (Swann 114). Ban Zhao’s demand of these qualifications reflects not only her self-identification with competent gentlemen, but also her confidence in women’s capacity to acquire genuine virtue, and then rule by virtue. Only with virtue and knowledge can a woman subversively touch on the fiefdom of men. Hence, although on the surface Ban Zhao emphasizes literacy and virtue merely as a recipe for husbands’ affection in Lessons, she essentially strives for women’s access to education, which prepares them to have a finger in the pie shared by men.

Even while expressing her ambitious aspirations for self-cultivation and political influence, Ban Zhao still adopts linguistic disguise to moderate her language in Traveling Eastward. At the end of this ode, Ban Zhao unexpectedly switches her aspirations from following the examples of virtuous people to “[being] pure” and “[wanting] little” (Swann 116). Given the Confucian traditions that encourage scholars to secure an official position to exercise government by virtue, Ban Zhao’s final objective of seeking innocence appears abrupt. In the Analects, Zixia, one of Confucius’s disciples claims that “having conducted [one’s] learning, one should take up official duties” (426). Zixia’s advice highlights that Confucianism considers virtue more as an elementary qualification for ruling than as the ultimate goal of learning. Aware of this tight bond between virtue and political power, Ban Zhao prudently camouflages her political ambitions through reiterating her lack of desire in Traveling Eastward. Besides her explicit assertion of “[wanting] little,” she models herself to Meng Gongchuo, a nameless gentleman who wins a modest reputation for his detachment from desire (Swann 116). Using the same disguise of a supportive and humble widow, Ban Zhao self-deprecates by calling herself “unenlightened” and “unintelligent” in the beginning of Lessons (178). Underneath the seemingly submissive contents of Lessons, Ban Zhao, in her own writing, exemplifies a form of linguistic disguise that enables women to cultivate themselves without arousing patriarchal suspicion.

Aware of the necessity for women to speak meekly, Ban Zhao sees the interrelation between women’s perceived moral characters and their reticence. Thus, she exhorts women to cultivate “womanly virtue” by speaking only “at appropriate times; and not weary others (with too much conversation)” (184-185). By reading Taming through the lens of Ban Zhao’s theoretical guidance, we can interpret Bianca’s silence, when Katherine interrogates her about her favourite suitor, as a performance that presents her “womanly virtue”. In particular, after witnessing Katherine’s rudeness towards Bianca, their father Baptisia indignantly questions Katherine, asking “when did [Bianca] cross thee with a bitter word” (II.i.31). Commending Bianca’s silence in response to Katherine’s insolence, Baptisia views Bianca’s scantiness in word as a reflection of her innocence in mind, which stimulates him to defend this faultless yet helpless daughter. In comparison, when later asked how she thinks about Katherine’s marriage with nutty Petruchio, Bianca comments that “being mad herself, she’s madly mated,” which displays remarkable ruthlessness in contrast to her previous forbearance (III.ii.152). Without any concern or pity for her elder sister, Bianca thinks Katherine deserves such a punitive marriage, which indicates her chronically repressed resentment and contempt towards her sister. But with her strategic silence, Bianca intentionally acts out her inability to independently make decisions, as a way to signify her need for male support. This adoption of silence not only wins her sympathy and support from men around her, but also consolidates her image as an innocent and virtuous lady. For instance, when Baptisia curses Katherine for abusing her sister, Bianca simply “stands aside,” weeping (II.i.25). In contrast to Katherine’s vociferousness, Bianca’s inconspicuous crying spurs her father to denounce Katherine for her “devilish spirit” (II.i.27). Positioning himself as a guardian of Bianca, Baptisia’s brutal criticism of Katherine highlights his intense feeling of justice and obligation in defending his younger daughter. Through her timely silence, Bianca creates a façade of incomparable vulnerability that triggers a sense of moral righteousness in men, who will choose to stand with her.

This illusion of her submission also lures men into believing that Bianca always sides with them, which makes men more willing to attach importance to her voice. In addition to her father’s partiality, Bianca’s meticulous choice of words catches Lucentio’s heart. Viewing Bianca as “sacred and sweet,” Lucentio compares her voice to “Minerva speak” (I.i.178, 84). Minerva is the Roman counterpart of Athena, Zeus’ daughter. As the daughter born from Zeus’ head, Athena symbolizes the wisdom generated from male thinking. By comparing Bianca to this pro-man goddess, Lucentio illuminates the self-serving nature of his trust in Bianca: he listens to Bianca only because he knows that her compliance and firm support of men will not give rise to aberrant behavior that deviates much from his intentions. Hence, when Biondello, one of Lucentio’s servants, urges his master to ask for Bianca’s hand in marriage, Lucentio does not agree with Biondello’s plan right away despite his eagerness for Bianca, temperately claiming that “I may, and I will, if she be so contended” (IV.v.95). Prioritizing Bianca’s choices, Lucentio’s initial uncertainty towards Bianca’s attitude indicates the power that Bianca’s words possess in determining their relationship. However, shortly afterwards, Lucentio consoles and asserts himself by assuming that “she will be pleased” by his proposal (IV.v.108). Such reassurance implies that the weight Lucentio attaches to Bianca’s voice functions merely as a retrievable reward for her assumed alignment with him. In short, Bianca’s volitional submission in language tricks Lucentio into standing by her, subtly yet effectively, when Lucentio was trying to win her affections.

In contrast to Bianca, who views language as a lubricant for her involvement in the male-dominated world, Katherine initially regards language as the sole medium for self-expression that can consolidate her identity, in the face of its erosion by men. For instance, when denied her voice by Petruchio when choosing her caps, she cogently argues that her tongue tells “the anger of [her] heart,” which sets her free, at least, “in words” (IV.iii.82-84). Besides showing her determination to defend her own voice from the overwhelming remarks from men, Katherine’s striving for expression illustrates her maladjustment to the patriarchy. Wielding her shrill tongue as a sword, she verbally attacks every instruction and expectation she receives from men. For instance, when Litio, the music schoolmaster, merely “[bows] her hand to teach her fingering,” Katherine immediately pays him back with “vile terms” (II.i.157,166). Although she sees the potential danger of “[being] made a fool” for a woman without “a spirit to resist” (III.ii.226), such an overreaction to Litio’s guidance reflects her persecution complex: she considers any guidance from men, even those out of good or neutral intentions, as a conspiracy against her. Hallett highlights this pathological rejection in his article “Kate’s Reversal in The Taming of the Shrew,” claiming that for Katherine, every occasion becomes an opportunity to “demand the opposite of what is required of her” (7). Katherine regards her shrewishness as the only outlet for her demand for self-assertion. Hence, despite knowing men’s inevitable aversion and hostility towards her cantankerousness, she still obstreperously carries her shrewishness into extremes, where she obsessively positions herself opposite to male expectations. Paradoxically, while indulging in her recalcitrance, Katherine simultaneously confines herself to the image of a shrew, which in turn limits her capacity to liberate herself from patriarchal doctrine. Hence, Katherine’s belligerent verbal explosions not only reveal her vehement rejection of male expectations, but also mirror a compulsive shrewishness that overrides her awareness of consequences.

Unexpectedly, Petruchio shakes this rigid shrewishness, not through adopting more acrimonious and pugnacious words like his future father-in-law Baptisia, but through his supportive and playful use of language that stirs Katherine’s static self-perception. He intentionally praises Katherine as “art pleasant, gamesome” and “passing courteous” even though he clearly knows that Katherine is aware of her notorious reputation as a shrew (II.i.259). Instead of considering these remarks as Petruchio’s taunts, Shakespeare scholar Tita Baumlin sees their healing and demiurgic effects on Katherine, motivating her to “[change] her sense of self, creating for her a new, more functional persona” (237). Since Katherine has condemned the entire species of men, Petruchio deliberately adopts such playful sarcasm to open a slim entry to her world. But he cannot touch Katherine without his appreciative reference to his mother: when Katherine asks where he studied such “goodly speech,” Petruchio attributes it to “[his] mother’s wit” without hesitation (II.i.277-278). Petruchio’s appreciation for women’s oratorical prowess demonstrates his respect for the lineage of female wisdom. Such respect shows Katherine the possibility of gaining men’s recognition through her eloquence rather than attracting dramatic attention to her peevishness. At the same time, Petruchio’s wisecrack, inherited from his mother, illustrates to Katherine a sensible use of language that does not brutally infuriate or alienate others. Hence, although Petruchio bluntly announces his aim of transforming her “from a wild Kate to a Kate conformable as other household Kates” (II.i.292-293), Katherine moves to accept this aggressive husband who seems so incompatible with her headstrong personality. When Petruchio barely misses their wedding, she weeps instead of celebrating its abortion. Her tears imply that underneath her gruff resistance to marriage, her confirmed self-alienation from society has begun to melt.

Katherine’s hovering over the brink of marriage seems to suggest a concession to impregnable male expectations. Yet Ban Zhao’s teachings about women’s respect and compliance in Lessons provide room for construing this “concession” differently. According to Ban Zhao, the relationship between a husband and wife follows the yin-yang philosophy (180). Women’s yin nature dooms their distinctive characteristics featured by “yielding” and “gentleness” (181). Given their perceived soft nature, Ban Zhao pinpoints that for women, “[to self-cultivate,] nothing equals respect for others. To counteract firmness nothing equals compliance” (181). Although throughout Lessons, Ban Zhao restrains herself from criticizing or challenging the existing female subordination dogma, here, she particularly emphasizes compliance as women’s optimal strategy to play against the flinty and unyielding male-dominated conventions. Thus, from Ban Zhao’s perspective, women’s compliance does not necessarily show a sign of concession; instead, it reveals the wisdom of evading hand-to-hand combat with overwhelming societal pressure. Through the lens of Ban Zhao’s teachings, Katherine’s increasing acceptance of her role as Petruchio’s wife does not imply a spineless relinquishment of her own identity, but sheds light on her increasing sophistication to “encounter [the] firmness” of the patriarchy, as well as flexibility to adjust to a new social position (Swann 181). Through Petruchio’s wooing, Katherine catches sight of the wisdom for women to soften their language, which motivates her to marry Petruchio as a first step towards assimilation into society.

Yet Katherine’s process of socialization requires her volitional acceptance of social conventions that comply with male expectations. To understand the paradoxical nature of women’ entrance to agency in the patriarchy, we need to refer to Ban Zhao’s observation of the correlation between a man’s social dignity and his wife’s obedience. In Lessons, Ban Zhao points out that a husband’s incompetence to control his wife illustrates his own unworthiness (181). Her perspective on men’s social reputations corresponds with the rationale behind men’s favor for a Stepford wife in Taming. In particular, after losing the wager on their spouses’ obedience due to Bianca’s defiance, Lucentio blames his beloved wife for making him a “fool” (V.ii.143). His unusual wrath underscores the importance of a wife’s compliance for her husband to manifest his intelligence and masculinity. This male reliance on female submission empowers women in a paradoxical fashion: women can only gain control over men precisely through their public subordination. Thus, Katherine’s monologue about male dominance at the end of the play, though seemingly submissive, exhibits her courage to admit women’s disadvantage and powerlessness in the patriarchy. As she admonishes, women’s “lances are but straws / Our strength as weak, our weakness past compare” (V.ii.189). By uncovering the emptiness of a tough female exterior, Katherine understands that women’s affirmation of their independent mind in the face of overwhelming repression from men lies not in women’s isolation from society, but in their capacity to cause men to relax vigilance against them. Starting from language, this process of social integration entails Katherine’s psychological journey of reflection and reposition, which eventually leaves her “at peace with her and her world” (Baumlin 247). Katherine’s adoption of performative obedience in language to preserve Petruchio’s male dignity marks her obtaining an inclusive selfhood that enables her to navigate the patriarchy.

In reward for her volitional submission, Petruchio, at least within their matrimony, releases Katherine from the shackles of the patriarchy. Literary critic Angelina Avedano reinterprets the cap scene, where Petruchio commands Katherine to “throw [her hat] underfoot,” in context of the social conventions during the Elizabethan era (V.ii.135-136). As she argues, since head coverings symbolize their “subjection to men and God” for Elizabethan women, Petruchio’s order for Katherine to remove her hat implies “both the assertion of Kate’s liberation as well as the couple’s decisive transcendence of cultural limitations” (116). By taking into account the emblem of head coverings, Avedano captures Katherine’s emerging emancipation in her reciprocal submission to Petruchio. However, since Petruchio takes pride in his competence to “man [his] haggard” through depriving Katherine of food and sleep, he at least accepts female inferiority, as advocated by the patriarchy (IV.i.193). Hence, Avedano’s reinterpretation exaggerates Petruchio’s rebellion against social norms. In comparison, Ban Zhao’s remark about a daughter-in-law’s relations to her husband’s family offers a more nuanced framework to understand the cap scene. Ban Zhao urges women to attain a family umbrella through their linguistic obedience. As she notes, “modesty and acquiescence,” which require a woman not to “dispute what is straight and what is crooked,” serve as her fundamental principles to win the affection of her husband’s family (187-188). Through acknowledging linguistic obedience as a concession of “personal opinions,” Ban Zhao prioritizes its long-term benefits: women’s “flaws and mistakes” get “hidden and unrevealed” (188). In the case of Katherine, she honored Petruchio in the wager with his brother-in-law with her performative obedience. In exchange, Petruchio offers her a breathing space in their marriage. Thus, Petruchio’s playful cap challenge to Katherine, instead of suggesting his genuine rebellion against male authority, reveals his tacit promise of Katherine’s “disobedience” in their family, as well as his willingness to cover it up. More importantly, this tacit collaboration with Petruchio reconstructs Katherine’s public image from an obnoxious shrew to a virtuous wife, which protects her against criticism and attack from the patriarchy. Thus, Katherine’s successful practice of linguistic disguise suggests that women’s avoidance of verbal confrontations, though restraining their self-expression, repays them with both a firm foothold in public, and marital rapport in private.

Although Katherine, Bianca, and Ban Zhao all succeed in adopting linguistic taming to strategically wrestle with the patriarchy, the extent of agency they gain through it differs. Compared to Bianca, who has grasped linguistic taming upon appearing on stage but still has to fake smiles even in the face of her husband, Katherine is fortunate enough to be allowed to express her true self, at least within the shelter of marriage. However, such “fortune,” at the mercy of Petruchio, requires Katherine’s brutal self-repression and shameless self-deprecation in public. Admittedly, such self-repression and self-deprecation do coincidentally enable Katherine to reconcile her obstinacy with patriarchal impositions, and thus reposition herself in the labyrinthine network of human relationships. However, these superficial benefits from practicing linguistic taming cannot cover up her limited agency and ultimate reliance on male power. Worse still, as Katherine alienates her sovereignty in public to her husband in exchange for marital asylum, she tacitly renounces her right to showcase her talents outside the domestic sphere.

In contrast, Bianca and Katherine’s imprisonment in the domestic sphere does not happen to Ban Zhao due to her widowhood. But when Ban Zhao lived in her husband’s family, she was also slaving at domestic labor “day and night” (Swann 178). Her humbleness and reticence then did not even slightly alleviate her constant “fear” and “distress” in such a captious environment (Swann 178). Only when Emperor He summoned Ban Zhao to his palace to educate the empress after her husband’s death, did Ban Zhao obtain an opportunity to give full play to her literacy and moral integrity (Swann 177). Hence, even for Ban Zhao, practicing linguistic taming did not help her chop off the shackles of domestic services. In light of the family trap imposed on Bianca and Katherine, linguistic taming is no more than a defensive strategy that buffers women against the brunt of the patriarchy. The agency afforded to women by linguistic taming still primarily depends on their husbands and fathers’ charity. The wisdom of linguistic taming advocated by Ban Zhao lies in its duality, by enabling women to transform the seeming weaknesses of their obedience to men, into essential tenacity that preserves them, to varying degrees, from direct confrontations with the patriarchy. At the same time, if mistakenly regarded as an ultimately powerful weapon to fight against the patriarchy, linguistic taming can only create an illusion of agency and empowerment for women, which will eventually diminish their strength to break away from male domination.

Works Cited

Avedano, Angelina. “Kate and Petruchio: Co-Heroes in an Alliance for Agency? Film Versions of Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew.” West Virginia University Philological Papers, vol. 54, 2011, pp. 112-118.

Ban Zhao. Lessons for Women. Translated by Swann, Nancy L., The Century Co., 1932.

Ban Zhao. Travelling Eastward. Translated by Swann, Nancy L., The Century Co., 1932.

Baumlin, Tita French. “Petruchio the Sophist and Language as Creation in The Taming of the Shrew.” Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, vol. 29, no. 2, 1989, pp. 237-257.

Chen, Yu-shih. “The Historical Template of Pan Chao’s Nū Chieh”. T’oung Pao, vol. 82, fasc. 4/5, 1996, pp. 229-257.

Confucius. The Analects. Translated by Ni, Peimin, Understanding the Analects of Confucius: A New Translation of Lunyu with Annotations, New York: State University of New York Press, 2017.

Hallett, Charles A. ‘“For she is changed, as she had never been’: Kate’s Reversal in The Taming of the Shrew.” Shakespeare Bulletin, vol. 20, no. 4, 2002, pp. 5-13.

He-Yin Zhen. “On the Revenge of Women” (女子复仇论). Translated by Liu, Lydia H. et al, The Birth of Chinese Feminism: Essential Texts in Transnational History, New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Shakespeare, William. The Taming of the Shrew. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2014. Print. Swann, Nancy L. Pan Chao: Foremost Woman Scholar of China. New York: The Century Co., 1932. Print.